John Singer Sargent Paintings in the Art Renewal Center

A portrait is a picture in which there is something not quite right nearly the oral cavity.

—John Singer Sargent

Portrait of Sarah Choate Sears, 1899

Probably one of the most renown portrait artists of the last century, John Vocalizer Sargent was born on January 12, 1856 in Florence, where his American family lived at the fourth dimension. Sargent'due south family unit travelled extensively throughout his childhood, and information technology was his Italian influences, namely Tintoretto for his vivid brushwork that would have a lasting impact on the young creative person. When Sargent trained under Carolus-Duran, a up-and-coming French painter from Lille, he taught Sargent about alla prima and the lively brushwork of Velázquez and drawing with the castor. This would lead Sargent to travel himself to Spain and written report Velázquez up shut, subsuming him into what would become Sargent's trademark sort of 'tight' impressionism that is ofttimes imitated today by portraitists. Despite this loose and vivacious brushwork Sargent's methods were extremely perfectionistic, to the betoken of being like Stanley Kubrick's space takes on a film set...Sargent was equally ruthless on numerous sittings (and pigment) to capture his subjects. Thick and generous amounts of paint were a key component of Sargent's brushstrokes, and if fifty-fifty the slightest problem appeared Sargent would scrape off the sheet completely and beginning all over again, oft numerous times.

In Portrait of Sarah Choate Sears above Sargent's fickle brushwork is hypnotic to come across upwardly shut. Paying particular attention to color temperatures and the use of light, he creates an elegant portrait of this famous American art collector too as artist and photographer from Massachusetts. Thick paint or not, Sargent e'er refined his edges carefully except in areas like his drapery, which he interpreted strictly in terms of color value and chroma. Her confront has deep graphic symbol and intelligence, which Sargent captures by paying shut attention to those eyes and the gracefulness of her easily. Note how he creates the illusion of transparency by strokes of pink on arms and neck. The eyebrows are merely a few strokes of raw umber.

The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882

This famous portrait of four young girls is a massive foursquare painting (87.6 in × 87.6 in) depicting the daughters of a wealthy American living in Paris. Many comparisons have been made of this painting to Las Meninas past Velázquez for its deep shadows and unusual system of the figures. Sargent places the two daughters in dark blueish-dark-green and white perpendicular to each other, with the second facing us, her face off center of the painting. The other faces the corner of the room leaning confronting the giant vase, sulking as if not wanting to exist there. Both are in shadow as if to suggest their possible conniving nature. The girl in red is in a vertical space by herself with the corner of the area carpeting pointing at her to imply her unique beauty and importance in the family, arms proudly behind her back. The adorable youngest is sitting on the rug playing with her doll, feet splayed together to heighten her innocence and undeveloped elegance. Sargent has captured the personalities and family ranking of these girls with a sophistication unremarkably given to adults, but hither they are highly individual and iconoclastic. The Classical formal family unit portrait is shattered for a more honest approach that tells more of who they are.

El Jaleo, 1882

Painted during his travels in Spain, Sargent had a keen fascination with gypsies and their music which he wanted to pigment on a larger scale. Lit suggestively from beneath with a looming shadow backside her, Sargent attempts to recreate the rhythms and passion of spanish guitars and sensuous movements. This type of bailiwick affair would have been indeed scandalous to European society who marginalized gypsies for their lack of work ethic and unusual superstitions. Here, Sargent exalts them as many artists did for their exuberance and joie de vivre. The sense of motion Sargent suggests by placing the dancer off middle towards the right, with her trunk leaning backward diagonally and arm in the air, mimicked by the women behind her against the wall suggests the contagious tempo of this hypnotic music.

The Breakfast Table, 1884

A loose study that seems most painted in ane sitting, Sargent conjures a strong sense of presence for such a simple field of study matter. Note the strong complementary colors with a contrast of round and rectangular shapes. A black wedge of emptiness from an open door behind the woman is the only night shadow in this painting, which is atypical for Sargent. Instead, he uses glass, silverware and prominent brights to heighten the mood of this scene, with absurd greys and greens with an eerie yellowish-dark-green glint of calorie-free on the wall behind her. Apparently Sargent'due south younger sister, Violet, she appears to be cutting an orangish while reading a book, and Sargent chooses to bandage a cool green shadow backside her, unusual yet mannerly at the aforementioned time. I love this painting because it is indifferent to us, the viewer, and doesn't try to gain our attention even so by color lonely information technology pulls united states in anyway. This is i of Sargent's most underrated works.

Sargent in his studio in Paris, 1885

This spacious studio is a testament to the success and prestige of Sargent as the leading artist of the Edwardian era. On his easel is The Breakfast Table.

An Artist in His Studio, 1904

A portrait of Ambrogio Raffele, a fellow landscape painter and friend of Sargent studies his own landscape paintings on the floor below his easel and on the bed, palette and brushes in hand. Despite the relatively cramped quarters Raffele is painting in, Sargent focuses on the painter's state of mind and how the thought procedure of painting takes united states away from the present moment within our own head. Here, Sargent paints a superb profile of Raffele, slightly foreshortened, with a solid construction to the head with smoothen edges. The mantle of his article of clothing is marked with vigorous brushwork...the back of the chair painted with thick xanthous-orangish tints. The shadow along the wall, especially on the pillows behind the large painting are warm and transparent. What Sargent apparently failed to learn from Velázquez notwithstanding, was the contrast of brushwork and using cleaner edges to highlight important areas, and in this painting the monotony of bedsheets to the right disrupts the composition. Had he left the footboard bare except for the pale bluish jacket and straw hat the painting would have improved profoundly, and the corner of the footboard pointing toward Raffele would take reinforced him as the focal signal. Another solution would have been to put the bluish jacket on Raffele while sitting in that chair instead of a dull, muted suit.

Portrait of Jean Joseph Marie Carries, 1880

In this intriguing study of sculptor Jean Joseph Marie Carries, Sargent makes the brushstrokes themselves behave similar clay, twisting and wrapping effectually the likeness of this studious fellow. It is clear that a work such every bit this helped greatly to pave the manner for modernist artists, yet there is still structure and emotion to the face. Sargent however pays attention to the optics and nose, and contrary to Sargent's quote well-nigh mouths Carries' lips appear quite normal. If anything it is his earlobe that appears totally unnatural and unfinished, drawing attention to itself. In spite of this, Sargent creates enough of presence.

Portrait of Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau), 1883

One of the most famous portraits of all fourth dimension, Sargent hoped this elegant and minimalist portrait would propel his career only instead caused an unusual controversy and ruined his reputation in France. Although tasteful and classy to our mod eyes, in the Edwardian and Belle Époque eras the style for women was to be seemingly covered from neck to ankle. This low neckline was apparently too much even for the French, and in the original her right strap was dangling off her shoulder. Had Sargent painted this a mere x years later or so in Paris the reception may have been different. The woman, Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau was an American who married a Parisian banker and hoped, like Sargent, that the painting would garner fame and attention for both of them when he premiered it at the Paris Salon. Gautreau was a high-contour socialite whose reputation was not quite innocent. Here Sargent defines her equally confident, head in profile to accentuate her sternocleidomastoid muscle of her cervix. Her cool skin alludes to an upper-course adult female, and the fashion Sargent has painted her hands shows an attention to detail and anatomy that he never bothered with before. Even the drapery of her dress is understated and accurate. Sargent captured something non quite seen before, a kind of vulnerability and sexual poise at the same time, gimmicky yet Classical— some even retrieve it was inspired by this Mannerist fresco. Information technology is unfortunate that a painting of this power would be criticised so much that Gautreau herself was utterly disappointed and humiliated by the negative reception...perhaps that profile looking away from the states proved too big-headed for french tastes, and oddly different Sargent as most of his subjects look at the viewer. Years after he sold information technology to the Met in New York, where it resides today.

Gondolier's Siesta, 1905

Ane of Sargent's many watercolor paintings, this is a medium that he was perfectly natural at. His many breathtaking vistas such every bit this view in Venice, and his various portraits, show his mastery of the medium and confidence in colour. The way he has suggested texture and light in the building behind the gondolieri, as well as the vibrant greens and reflections under their boats shows he was proficient at many mediums, as he was with the languages he spoke growing upwards in Europe.

Portrait of James Whitcomb Riley, 1903

Sargent's portrait of this American author shows a great maturity in his style, with superb attention to edges and incredibly subtle blending in the pare tones of this hitting face up. A cerise complexion with pensive eyes, small-rimmed glasses, distinctive nose and a mouth that is palpably elderly reveals a sensitive portrait of an intelligent man. The dark, warm groundwork serves to raise the drama and soul of this writer of works such every bit Little Orphan Annie. This is a portrait Velázquez would have been impressed by.

Henry Lee Higginson, 1903

The founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Higginson was a prominent American banker and philanthropist. In this portrait, Sargent creates an air of mystery and deep grapheme, using the background as an element in the painting with the strong glint of golden calorie-free on the wall. A uncomplicated palette by Sargent'south standards, with about no drapery or folds, leads the states to focus on the confront of this man staring at us without any hesitation, bathed in a warm calorie-free. Sargent's power to experiment and discover new ideas in palette and costume to suit the personality of the sitter is worth noting and deserving of respect, as many artists seem to get more than formulaic with their success.

In a Garden, Corfu, 1873

I like this painting because it does non resemble any of Sargent'south works. Deeply Classical in spirit and execution, Sargent takes a woman reading exterior as something from the Renaissance or early Rococo. The smoothness of her skin and graceful contour, reading side by side to a big vase against a bright background heaven that appears to be painted over, is quite surreal. Note the other two women on either side of her reading also, like bookends. The massive canopy of a tree above them frames the composition to enhance the peacefulness of this at-home afternoon.

Interior of Dodges Palace, 1898

Despite its drama and intensity, this Venetian interior was painted on a relatively pocket-size scale for Sargent (nineteen.8 × 27.ii in) but is no small painting. The study of warm sunlight bathing a rich interior of this splendor with authentic attention to color temperatures is a real masterwork. Squint and it looks lifelike. Note the streaks of colour in the smooth marble floor.

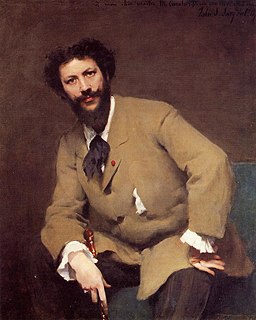

Carolus-Duran, 1879

This famous portrait is of Sargent's art instructor and captures the essence of this confident artist, right down to the texture and color of his coat against the warm reddish background. An before work, ane can see that despite technical proficiency, presence and understanding of the sitter, its straightforward pose and gaze lacks any real psychological insight, compared to his later piece of work.

Street in Venice, 1882

Some other early work, this moody street in ane-point perspective is full of graphic symbol. Silhouetted figures against a near empty street with a woman walking past timidly...Sargent was channeling picture palace before its time. The ability to tell a story in painting is enormously powerful, even when simplistic, and here it makes us desire to be in that location, somehow. The quality of low-cal here, using a warm depression-central palette, is dreamy, unreal. All that is missing are the details of signs and door entrances.

Repose, 1911

A later work, Sargent's mastery is evident here with brushstrokes that advise shimmering material from bright afternoon window-light bathing her. The pose is interesting in that her hands are crossed, all the same she lays back, tired as if indifferent to being painted or observed by anyone, and it gives a psychology to the painting that is unique from all of his other work. Her torso is wrapped like a package, perhaps a sweater of some sort, and she seems too tired to fight the oppression of this costume. Perhaps Sargent himself was tired of how women were being portrayed as loftier-manner princesses, and instead of revealing her trunk he instead portrays her similar article of furniture, stiff and bad-mannered, and tired.

Sargent's legacy would accept a lasting bear on on art and portraiture, and although in this blog I accept more than once indicated how overrated his status is, peculiarly to current portrait artists who try unsuccessfully to imitate him without studying the past, his fine art is worth studying. He adopted the methods of the past to suit the Edwardian era he lived in, and he did information technology well. And he never stopped experimenting or learning. Greatness comes from taking risks and expressing all that is inside yous, not but seeking fame or fortune.

Source: https://besidetheeasel.blogspot.com/2013/01/john-singer-sargent.html

0 Response to "John Singer Sargent Paintings in the Art Renewal Center"

Post a Comment